The truth about going mega-viral, part one

“Find what you love, and let it kill you.”

In 2005, I wrote this Charles Bukowski quote1 on a Post-It and displayed it over my monitor at my San Francisco ad agency job, where I spent eighty-plus hours a week, including regular overnights, plied with Adderall from the boss’s stash. This was a normal part of our office’s—and advertising’s—culture; overwork was not only expected, but worn as a badge of honor. I carried my BlackBerry with pride, thrilled to be deemed important enough that the agency wanted me reachable at all times.

That same year, Steve Jobs gave a now-legendary commencement speech at Stanford, in which he said, “The only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do.”

And I believed him. I’d graduated college in 1998 and moved to San Francisco in the first dot-com boom, finding work at a well-funded media startup with a seemingly nonexistent business model.2 At our weekly all-hands meetings, our handsome and charismatic (white, male) founder shouted into a headset about purpose and passion, growth and expansion. We were on a mission to change the world together—through the distribution of a weekly print magazine about the Internet. We all cheered and ate free sushi for dinner, then went back to work.

Work was how I felt good about myself; it was how I crafted a post-college identity, and I was excellent at it. As the 90s gave way to the millennium, the idea that work should be synonymous with passion and purpose took an even firmer grip on American culture. Steve Jobs was no dummy when he preached the gospel of Do What You Love; he knew if his employees believed they were designing computers, they’d want to see their families (their friends, the sky). But if they believed they were changing the world, they’d willingly spend their nights, weekends, and holidays at the office. Corporate productivity skyrocketed, and the only additional cost to our employers’ bottom lines was feeding us late-night takeout and sending us home in a cab when we were too sleep-deprived to legally drive.

If work was my purpose, my noblest calling was to find what I loved, and let it kill me. For eight years of my 20s and 30s, I put that energy into my advertising career, where we weren’t selling cell phones, we were changing the world through connectivity. I am more than a little embarrassed to admit I was willing to let making insurance commercials kill me— especially after having survived actual cancer?— but it also demonstrates how deeply seductive this narrative was, and how seriously I took it.

What I am saying is that, by the time I quit advertising to start my own business, I believed completely in the fantasy of all-consuming work as the road to personal fulfillment. And this was 2010, the early days of social media, when the entrepreneurship-fetish train was just leaving the station. “Hustle culture,” #ThankGodItsMonday, #Girlboss, Boss Babe, Mompreneurs, Leaning In: all of that was still to come, and would be neatly aligned with the early years of my company.

So when I built something I actually loved and truly believed in—something that was mine, something I felt could actually, maybe, change a little bit of the world for real? I went all in.

To be clear: this story is not about placing blame, or failing to take responsibility for my choices. I own them all. This is about understanding how I navigated success; how confusing it felt to hate my life while “living the dream;” what years of viral growth ultimately cost me; what I learned about sustainable change on the way; and, eventually, how I found my way out. (Spoiler alert: still working on it.)

Living the Dream

The morning of May 23, 2015, I was sitting in the back of a black town car drinking a quad-shot iced espresso, which I had already spilled on my white shirt, twice. The car inched and honked its way across Manhattan from my shitty hotel—a place with tiny, windowless rooms and stainless steel bunk beds, like some sort of prison that costs three hundred and fifty dollars a night—to ABC, where tomorrow I would be a guest on Good Morning America.

My hands shook from too much caffeine, too little sleep, having forgotten to eat food, and the general state of being myself at that point in time. I was keenly aware that I was supposed to be happy, but I was brittle and exhausted.

When you are a guest on Good Morning America, they send a car for you—“send a car,” like you’re Brad Pitt—the day before, which takes you to the studio for a pre-interview session. This session is when you show them what you’re planning to wear on TV, and they judge you while you try not to laugh or cry, both of which will seem like plausible reactions to the situation at hand.

The Good Morning America wardrobe supervisor, a slim, blonde man with tight, poreless skin, was somewhere between twenty-six and sixty years old. His job, or part of it anyway, was to instruct me to slowly turn around in a circle while he assessed how close or far away I was from being acceptable for television. Halfway through my turn, he picked up his walkie-talkie: “She’s gonna need some foundation garments.” (When imagining his delivery, think David from Schitt’s Creek.)

I was wearing a seven-year-old bra from Target. So I guess I didn’t disagree?

My underwear didn’t pass the test, and neither did the dress or cardigan I brought to wear on air. The wardrobe guy escorted me down to the wardrobe closet in the basement of the basement, explaining that after this, they would send another car to take me back across town to some kind of secret shapewear store for TV people. The women at the store would be waiting for me, he said. They know you’re coming. Like wrangling my back fat was a tactical, coordinated mission between the CIA and FBI.

The wardrobe closet was less of a closet and more of an enormous room stuffed with rolling racks of dresses and heels and tailored news-anchor blazers. The intention was to find me an outfit, but this plan went awry when it suddenly dawned on them that I was a size 14 and the biggest clothes they had were a 6. There was a discussion about where one could possibly find TV-appropriate clothing in plus size in Manhattan, a city of ten million people. A third person was summoned to help solve this highly complex problem, and it was determined that Macy’s was the only option.

It was at Macy’s, trying to explain to the personal shopper that I would not be buying a $700 kimono, where I began to laugh and cry at the same time. The shopper backed out of the room, kimono in hand. I slid to the floor, face-down, cheek pressed to the disgusting Macy’s carpet, while my phone buzzed with things requiring my immediate attention.

I tried and failed, again, to summon happiness. I was a Successful Entrepreneur! I was about to go on national television to talk about my work—work I was truly proud of! Everything I’d ever believed about work, the role of work, the purpose of work, the purpose of me: it all laddered into this big moment of success.

This was supposed to feel amazing. But my brain buzzed. My head ached. I struggled to formulate a thought. And all I wanted was for everything to stop.

In addition to being a person whose mouth was now an inch from the floor of a Macy’s dressing room, I was also the founder, CEO, writer, and artist of Emily McDowell Studio3, a greeting card company designed to help people connect and heal. In the three years since our launch, the brand had grown beyond anything I could have imagined. And one week earlier, we’d introduced a new collection called Empathy Cards4, which were now a global news story. Hence my appearance on Good Morning America.

In a single 3-week period in 2015, my company, my work, and my personal story of cancer survivorship5 were featured in 300 major media outlets in 22 countries. I did public radio in Ireland, Australia, and South Africa. BBC. Al-Jazeera. NPR. CNN. NBC Nightly News. Bloomberg Business. And yes, Good Morning America.6

To my half-million social media followers, I was living the dream #girlboss merch was made of. But the truth was that I fantasized, daily, about coming down with an illness that would be bad enough to hospitalize but not kill me, like some sort of mild coma minus any long-term effects. I would have told anyone (and did!) that I had my dream job, yet I was desperate to escape it, and the only means I was willing to mentally justify this with was a hospital stay.

I was living the dream—the dream of every company founder, the dream of “blowing up,” of constant demand for my products, of viral success and exposure and growth, growth, growth. It was everything I wanted. I had found what I loved.

And it was killing me.

In the three years leading up to this wave of publicity, Emily McDowell Studio was already growing much faster than I could thoughtfully or strategically manage. The first greeting card I ever made, a Valentine I sold on Etsy, then my side gig while I freelanced, went viral hours after it went up. I sold 1,700 cards in a week, which was thrilling—and a huge logistical challenge to manage from my apartment. I took its popularity as proof of concept, and got to work on creating a brand.

Three months later, at the launch of my first wholesale collection, I received a 15,000-card order from Urban Outfitters. They gave me two weeks to fulfill it before it would be cancelled. Wholesale card orders require individual packaging, which is a tedious, manual operation. I had five days to find a studio space to rent in Los Angeles that could take immediate delivery of multiple pallets, and a crew of ten-plus people to help me prepare the shipments. And, oh yeah, I hadn’t yet printed the cards, only samples.

The only alternative was saying no—and no was not an option. The order was a Big Deal. The challenge, the adrenaline, was exciting. My work would be in stores nationwide! It was all happening! I got the order out. And then, from day one, I was chasing after the company, reacting instead of planning.

A product-based business lives and dies by projections: inventory, cash flow, manufacturing. But going viral makes it impossible to plan, and we did, more times than I can count. We would catch our breath, and then another one of our products would hit the front page of Reddit, or a celebrity would tweet a photo, and I’d wake up in the morning to thousands of orders for something that was sold out. In 2014, one of our cards was the top-selling item—not card—on all of Etsy.

Eight months after the wholesale launch, we had 120 sales reps and thousands of retailers. Our growth trajectory was so steep that we were essentially a different company every few months, which meant every time we invested time and money into solving a problem, we’d need a different solution almost as soon as we got it implemented. This is a very organized way of saying that despite everyone’s best efforts, our back-end was a perpetual shit show.

The constant reinvention, which felt exciting in year one, became exhausting and demoralizing by year three, yet I kept hearing how lucky we were to have “good problems.” I didn’t feel like I could complain, because all the hardship was a byproduct of success. I was living my purpose, building a brand with my name on it, making mission-driven work I believed in. Everyone kept telling me what a great job I was doing, because we were profitable and growing, which were the agreed-upon metrics of success. But instead of feeling fulfilled, I was brittle, hollow, overwhelmed. And confused.

I assumed the reason I wasn’t having more fun was me not doing my job well enough, so I doubled down, vowing to put the company first, no matter what. The more people we hired, the more responsibility I felt to not let them down, so I kept adding more to my plate. I stopped sleeping, stopped feeding myself actual food, stopped moving from my chair for eight hours at a time, holding my pee until I got one more thing done, stopped everything except producing and grinding and delivering.

What was I grinding on? Products that were dedicated to addressing mental health, imperfection, and human connection.

If it wasn’t so fucked-up, it would be funny.

This is where I was—and where the company was—in May of 2015. And then, we became a global news story, and our revenue doubled overnight.

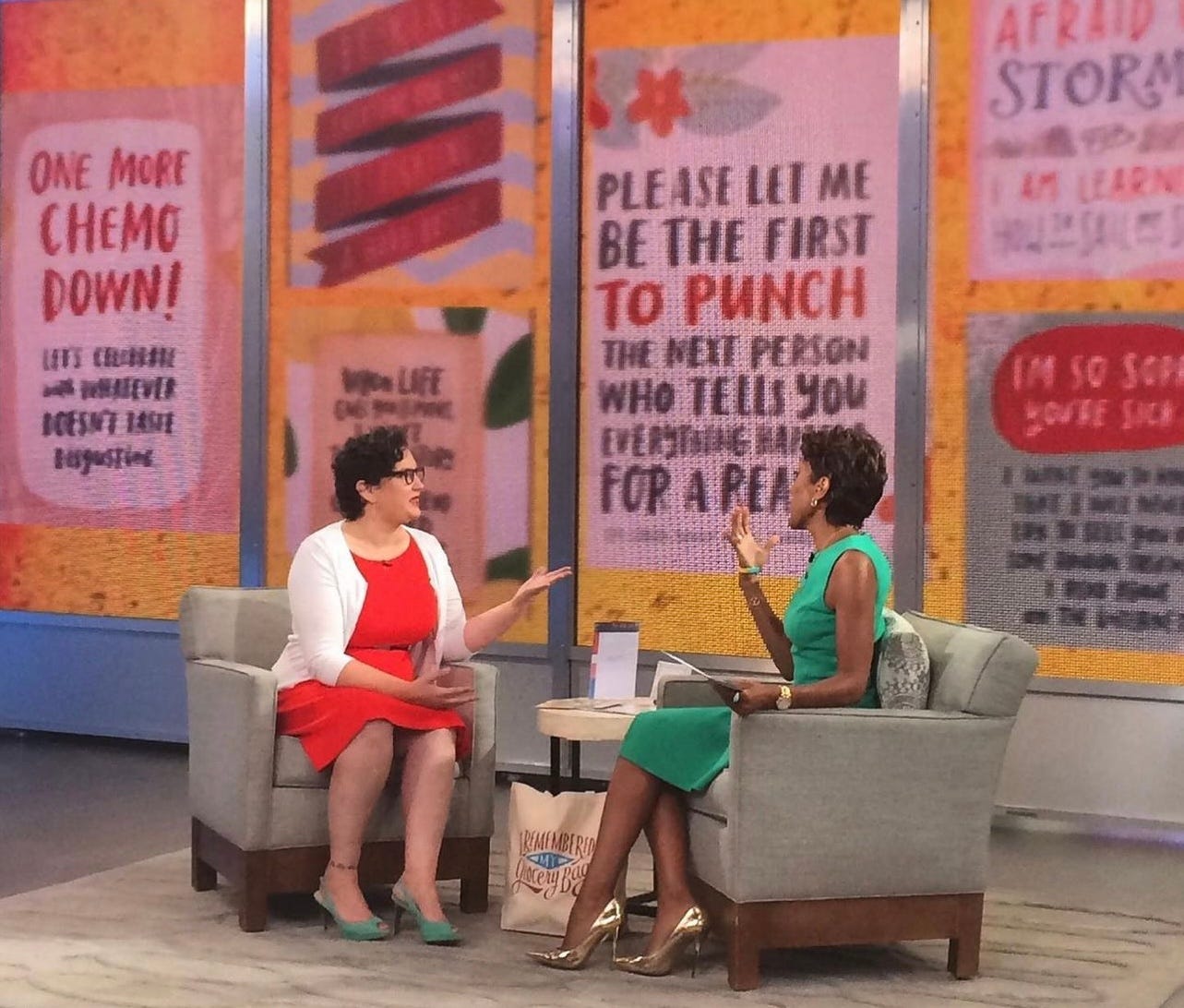

Talking with (the very nice, very tall) Robin Roberts on GMA, not wearing a $700 kimono

As part of the Empathy Cards media blitz, NBC News ran a special segment about my company, sending a five-person crew to Los Angeles, who spent two days filming me at work and home. They shot me in my kitchen, pretending to chop carrots for dinner, as if I lived on anything but Starbucks, Clif Bars, and Xanax. They shot me on my front steps, looking thoughtfully into the distance, as if I allowed myself time to sit and ponder things. They shot me posed on the couch with my partner and his ten-year-old son, pretending to laugh at each other, as if I actually hung out on the couch with my family, as if I didn’t work 14 hours a day.

And then they cut it all together into a montage of me, pretending to have a life that was not my life at all, and they aired it.

It was the same narrative we’ve all seen a million times: the go-getter founder smiling with a TV host, smiling and pointing to an ON AIR sign, smiling while holding up a gigantic coffee, smiling while someone throws rainbow glitter on her, smiling with her mouth open big and wide, mid-laugh, like she’s having the best time EVER, because the kind of success she’s spent years toiling for and dreaming about and putting on a Pinterest board is now hers.

This narrative has sold a shitload of conference tickets, digital courses, and coaching packages, but it wasn’t my real life, and it isn’t anyone’s real life. It’s a fabrication.

Revenue doubling overnight! Sounds great, right? But this was the reality:

The media onslaught was beyond anything I could have possibly imagined, and yes, it was wonderful, and it was also absolutely too much for me, for my nervous system, and for my little company’s infrastructure.

We got over 100,000 online orders in five days. The nationwide temp agency Apple One has three Los Angeles offices, and in one fell swoop, we hired everyone they had available—30 temps—to pack and ship orders and do customer service. Which first required teaching them how to do all that.

Most of my staff and I weren’t even in our office to manage this process, because we were in New York doing a trade show for retailers when all the press hit—the show that was otherwise our biggest, most complex undertaking of the year.

We ran out of product the first day. Normal printing takes a few weeks to turn around, so we had to order faster reprints using a digital printing method that was 5x the cost of our normal cards, killing the profit margin.

Because the cards addressed major illness, grief, and loss—things people desperately wanted and needed to talk about—I personally received thousands of emails from folks sharing the stories of the hardest things that had ever happened to them. Things that deserved a response. I couldn’t possibly respond to it all, and I felt like I was letting everybody down.

There was a flood of collaboration requests, honestly too many to count, from publishers, agents, other brands, writers who wanted to work with/for us, Big Pharma7, and people who wanted us to make cards for everything under the sun, all wanting to strike while the iron was hot; in other words, say yes right now or lose this opportunity.

There was no way I could hold all of this. It was too much.

I am very aware, as I write this, of my desire to not sound ungrateful for my success. I want to make sure you, stranger-reading-this, understand how much I appreciate the opportunities I’ve had, how fortunate I feel, how I don’t take success for granted. And yet, I am also aware that I’ve spent the last five years working to recover from it.

I have autoimmune disease, chronic inflammation, a nervous system that was stuck for years in fight-or-flight, a body that no longer makes cortisol. I’m afraid to take on projects with deadlines. I struggle at times to trust my judgment. And I have come so, so far from how sick I was five years ago, when my baseline state was perpetual, mild panic that never lifted, even in my sleep. And still—still—I worry I might sound ungrateful. This is how deep the conditioning runs, how insidious the belief, that success and exposure and growth and achievement and money are the goal, and that reaching the goal is something that warrants gratitude, no matter what.

When I couldn’t keep up with the rocket ship—when the velocity of growth began to destroy me—it felt like a personal failing, not an impossible setup. But no person is equipped to handle so much, so fast. What I didn’t know, what was never talked about, was that it requires time to metabolize success. No matter how hard you try, a human nervous system (and the ecosystem of a company) can only take in so much at once before it becomes unsustainable. And, of course, growth is often not the answer.

In the second part of this piece, I’ll talk more about these things— the metabolism of success, the practical lessons I learned from all this, things to consider when scaling, arguments for slow expansion or not expanding at all— all the business stuff. And what came after 2015, and how and why things got harder before they were easier. And how I found—am still finding—my way back to being a whole person.

Thanks for being here.

This is most often attributed to Bukowski; apparently there’s some question about whether or not it was actually him. Don’t @ me.

It would go under in 2000 after burning through hundreds of millions of dollars, so I think I was probably right.

Now called Em & Friends and owned by Union Square & Co., the publishing division of Barnes & Noble.

I created Empathy Cards to be a more honest and supportive alternative to traditional sympathy and “get well soon!” cards, which at the time were mostly limited to empty platitudes. This kind of card is now common, but back then, it didn’t exist. I had cancer in my 20s, so I’d experienced this firsthand—both the disappearing acts from people who were uncomfortable with illness, and the awkward way a “get well soon!” card hits when you might not.

The cards struck a nerve, and expressed things that millions of people had thought about, discussed with fellow survivors, but were not yet reflected in the world of sympathy cards: the one thing people all over the world traditionally send each other when shit is bad. This is why they became international news.

Fun fact: in online news stories, the journalist doesn’t get to write the headline. Headlines are written based on whatever the newsroom thinks will get the most clicks, since that’s how they make money. Which meant in my case, that despite being careful to never criticize my own family and friends’ responses to my illness, most of the headlines said things like CANCER SURVIVOR WRITES THE CARDS SHE WISHES SHE’D RECEIVED FROM HER FAMILY AND FRIENDS. So that was a little tough.

Another fun fact: As I was boarding the plane for New York to do GMA, Gayle King called me (herself?!) to try and convince me to bail on GMA and do her show instead, which was… a lot. Morning shows are incredibly cut-throat and competitive, which I didn’t know because The Morning Show was still four years away from airing. Normally, a PR person would shield you from this stuff, but I didn’t have one, because I’d done all my own PR. (I was, however, very lucky and privileged to have a kind friend whose equally kind husband was a retired heavy hitter in media. They were a lifeline when shit got crazy during this time; their guidance was a godsend.)

A number of pharmaceutical companies (and ad agencies on their behalf) asked me to write cards for specific conditions, to function as marketing for the drugs they sell to treat those conditions. The answer has always been no and will continue to be no. I said no to one last week! The idea that I would say yes to this request is, for lack of a better word, batshit.

“This narrative has sold a shitload of conference tickets, digital courses, and coaching packages, but it wasn't my real life, and it isn't anyone's real life. It's a fabrication.”

Thank you for that brilliant piece of truth. It’s what a o many hard-working artists/designers /entrepreneurs need to know.

I was an entrepreneur for the last 30 years ..working my ass off doing the trade shows crying at 11 o’clock at night while I’m taking down the booth by myself and questioning why, when I tell people I’m busy and they say well that’s a good problem ,I feel bad for complaining well all the while I’m exhausted mess.

I never got the fame that you did. I watched all of the companies with the cool girls at the helm and wondered how the heck did you do it?

I thank you from the bottom of my heart for sharing!

PS I am a neighbor right down the street and I’d love to have you over to my garden some time for some tea☺️

Welcome to hell! Lolslol kidding. I love you so much and what a fucking treat to read you regularly, Emily McDowell, Writer. Thank you for your craft and thank you for your words and thank you for making me cry but laugh in an aesthetically pleasing content environment.