Hi, friends.

My mom was diagnosed with cancer on June 7th and died on June 23rd.

For the last two months, I’ve been able to do the part of my job where I help others navigate their lives, but every time I’ve sat down to write a newsletter about my own, I just haven’t known where to begin. I’ve opened Substack, then immediately navigated away to do critical things like purchase an as-seen-on-TV toilet cleaning system on Amazon (haven’t tried it yet, will let you know) and Google why so many people in Switzerland are wealthy (pharmaceuticals and something about banking).

Thank you to the 90% of my paid subscribers who’ve stuck around despite my absence; I really appreciate your support. (And to the other 10%, I get it! No hard feelings.)

My mother was my greatest teacher, but the thing about great teachers is their classes aren’t easy.

I loved and respected my mom very much, and our relationship was also difficult and complicated, forty years’ worth of navigating knots and distance. In 1994, I moved from my childhood home in Boston to the Midwest for college, and the rest of our visits after that were me flying to see her; she never came to witness how I lived, to see what my world was like. But I know she was very proud of me.

When you lose a parent, the world offers condolences and assumes a certain kind of grief—consuming, devastating, waves of remembering that knock you down while you’re buying pickles at Safeway, the earth knocked off its axis. My grief has not felt like this, and I can’t quite tell you what it feels like, or if the feeling is anything I can even recognize as grief, but it is something. In 2009, my friend Carvell Wallace told me he felt closer to his mother after her death than he ever did while she was alive, and this feels true for me, too.

Despite the nature of our relationship, or maybe because of it, I don’t know—I can tell you it felt spiritually necessary to be present with her in the last days of her life, and to read four hundred pages of The Lord of the Rings aloud to her after she’d lost consciousness, and when it was time, to take her hand and walk her to the edge of the river, as far as I could go.

For my whole life, the people closest to me have said write about your mom but I never have, for a lot of reasons, and these stories aren’t a newsletter, they’re a book, and probably one I won’t write. There are as many versions of the truth as there are members in a family, and all of us are unreliable narrators. And it gets even more complicated when a character in your memoir is a public figure, with their own legacy.

But today, I do want to write a bit about my mom, to show you what a strange and brilliant star she was, and to celebrate the beautiful contributions she made to the world.

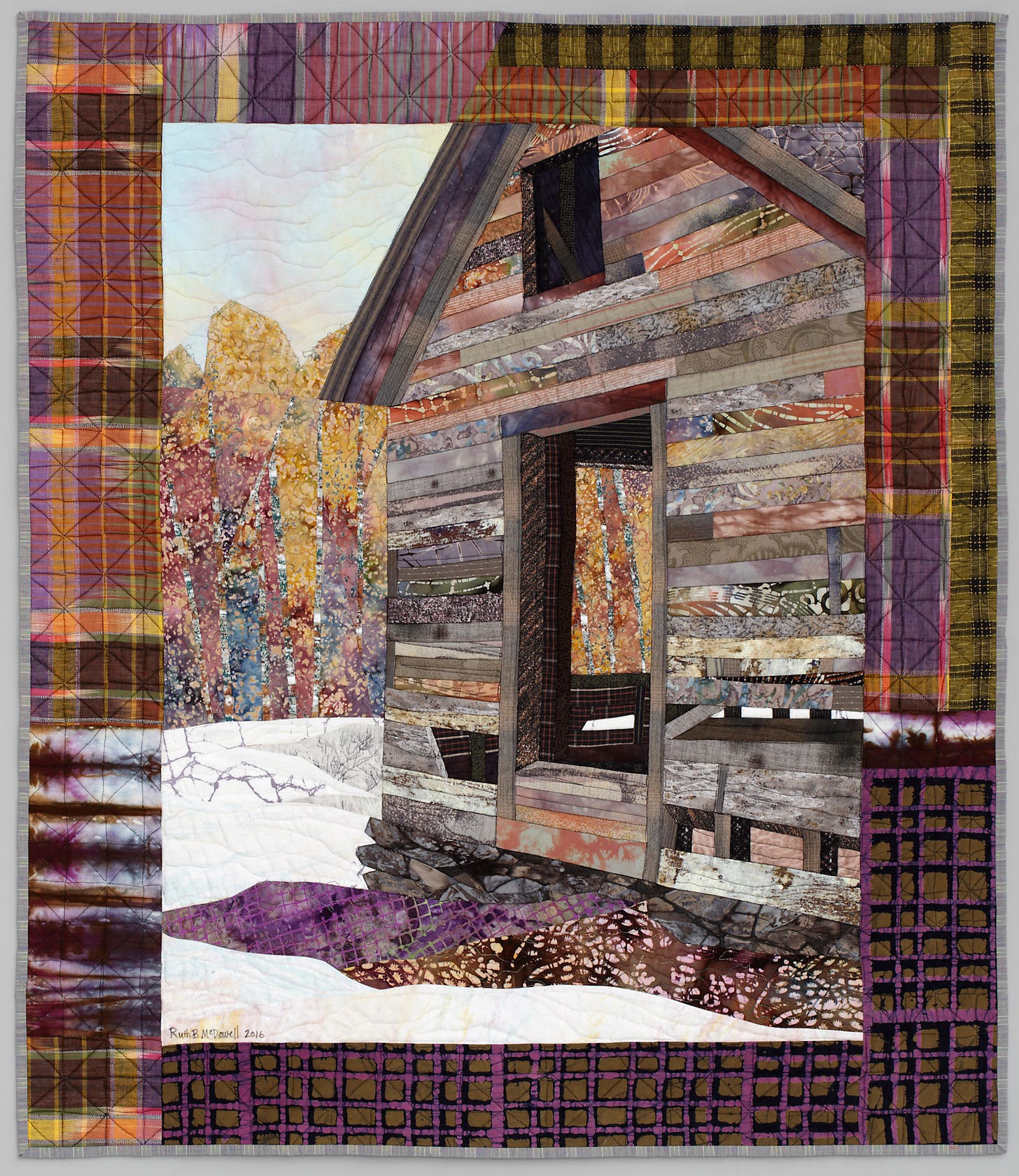

This is a quilt, not a painting(!). “Passages,” 2016, by Ruth B. McDowell; 37” x 32,” machine pieced, machine quilted, cotton fabrics, cotton batting; private collection.

My mother’s name was Ruth B. McDowell, and she was an internationally known artist and pioneer in the field of contemporary quilting, with over six hundred quilts to her credit in a career spanning nearly fifty years. As a child, I was embarrassed by her propensity to announce “I’m world famous, you know,” when she felt dismissed or underestimated, which was frequently. But she was world famous, in her niche, before social media or even the internet, in a time when fame was rarer and more meaningful.

My mom was a visionary and a genius who held everyone in her orbit to unforgiving standards, but only because she held herself to them first. She was one of a handful of women in her graduating class at MIT, and she would be annoyed if I shared that piece of information without also sharing that she hated every second of it and only went there to please her father, which was a mistake. She would want me to tell you “it’s a mistake to do things in an attempt to make other people happy, and that it’s important to do what YOU want to do.” (The you would be in all caps.)

She was a single parent to my sister Leah and me when that was a rare thing, too, and she figured out how to support us by making and selling quilts — “for the wall, not the bed” — and later teaching, lecturing, and writing books, before any of that was culturally established as a viable life path. She showed me it was possible to figure out how to do, and be, anything I wanted.

“Blue Clematis,” 2008, by Ruth B. McDowell; 35” x 31,” machine pieced, machine quilted, cotton fabrics, cotton batting; private collection.

For over three decades, she taught design and piecing workshops in person to thousands of quilters all over the world, and by all accounts she was an incredible teacher, beloved by her students. When we announced her death on Facebook, her long-dormant page—which she’d abandoned after one of her pieces went viral and she was inundated with “idiots who wanted to buy patterns”—was filled with hundreds of comments from folks grieving her passing. Her influence was massive, both in the medium of quilting and in the work of the people she taught, many of whom came back to her workshops over and over.

My mother generated work with her hands at a speed and volume I’ve never seen in anyone else; when she wasn’t officially working on a quilt, she was knitting or crocheting or beading, or building furniture out of branches cut from trees on her land, or weaving baskets, or embroidering, always her own designs. The house I grew up in had an enormous spiral staircase at its center, and she covered the stairs and second floor landing in an intricately patterned, wall-to-wall needlepoint carpet. Going through her apartment, we found 38 hats and 23 scarves she’d knitted in the last couple of years; these were just the ones left over, after she’d given away most of what she made.

In 2021, when my sister Leah and I moved her from her cabin on 12 wooded acres in Western Massachusetts to a senior apartment close to Leah in Minnesota, we asked her how long it had been since she’d washed her kitchen floor. She said she’d done it once after she moved into the house in 2007, but the water had warped the hardwood, so she never bothered with it again. My mother had endless energy for the things she wanted to do, and zero tolerance for things she thought were stupid or a waste of time.

The belongings we packed up and moved included several boxes of shells, sticks, rocks, pinecones, and birds’ nests, a 32-year-old portable fan, and five DVDs.

“Bison at Mission Creek,” 2008, by Ruth B. McDowell; 82” x 80,” machine pieced, machine quilted, cotton fabrics, cotton batting; private collection.

Many art quilters prefer to use fabric in solid colors, or to dye their own fabrics in order to get the exact colors they want, but my mom reveled in the challenge of using commercially printed, patterned fabric. She loved working with plaids, large and small scaled florals, tweeds, polka dots, African, Scandinavian, and Japanese prints, cut-up shirts from rummage sales, vintage finds. All these unexpected, odd, and often objectively hideous fabrics added richness and detail to her work, and tangible references to places and periods of time, an element she felt was important.

She explained all this, in her last weeks of life, to the nurses and doctors who rotated in and out of her hospital room. “A piece of fabric that looks ugly by itself sometimes turns out to be exactly what the quilt needs.”

The move to the Minnesota apartment a few years ago meant culling her vast collection of fabric down to about 1,000 pounds (fourteen large Home Depot moving boxes) and reassembling it on floor-to-ceiling bookshelves in the larger of the two bedrooms. She requested that after her death, we distribute the fabric to as many quilters as possible, along with instructions to incorporate it into their own work. “But I want them to do it in their own style, not to make a Ruth McDowell quilt.” When we announced on Facebook that we’d be sending out boxes of her fabric to anyone who’d like one, we got 800 requests in 45 minutes.

My nephew helping with the fabric distribution process (we had enough fabric to make 250 boxes!)

About a week before my mom passed away, she was moved to a different unit, and her new nurse approached me in the hallway. “I know who your mom is,” she said. “My mother had all her books.”

“The room with the best view just opened up. She can see the dome of the Capitol Building all lit up at night. I think we should move her.”

It was the last day she was lucid.

“Sumac 4,” 2016, by Ruth B. McDowell; 42” x 33,” machine pieced, machine quilted, cotton fabrics, cotton batting; private collection.

Mom was uneasy around technology; it made her anxious, I think because she couldn’t see or understand what made it work. Starting around 1993, every electronic appliance in her home was adorned with sticky notes featuring carefully drawn diagrams and instructions for its use. She never wanted a smart phone, or to learn texting or Zoom. When I visited in May, I saw she’d annotated the “door open” and “door close” symbols in her building’s public elevator with hand-drawn text signage. When I returned a few weeks later, someone had taken them down.

This spring, I started working on a new site for her; the old one had been built by a friend of mine in 2001 and was never updated, except to add tiny photos of new work.

I grew up surrounded by the quilts, and therefore took them for granted. Yeah, of course they were incredible, but they were also just always there, hanging above the old sofa in the living room.

But in putting her site together, I was struck, all over again, by the depth and expanse of her talent and vision; I invite you to take a look.

I love you, Mom.

I know it was hard for you to feel at ease here.

May the trees welcome you back home. May you be embraced like a long-lost friend by the songbirds and moss-covered rocks. And may you burst open with joy like a star, raining down into the wildflowers that return and return and return.

Mom on a teaching trip, mid 1980s. Her necklace is handmade; it’s an oyster shell with tiny pebbles and shells glued inside.

As always, thank you for reading, and for being here.

More soon.

PS: Indirectly related… I also want to share something else today.

One of my most beloved mentor-teachers, Robin Rice, has been releasing her memoir Stories About Stories as a podcast, one chapter at a time. It’s gorgeous and terrible and beautiful, about survival and awakening, and the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we tell others, and the distance between the two. It’s also designed to help listeners uncover, discover, and make sense of our own stories; each chapter is accompanied by questions and writing prompts. I’m completely hooked on it, and the timing of its release has been uncanny for me personally, as I sort through the stories I’ve told, and the ones I want to tell. Stories About Stories is free, and you can listen to it on Spotify here and on Apple here.

Damn Emily. What a thing it is to be raised by a blazing sun. You’ve done a beautiful job sharing a glint of your mom with us and I can only imagine what an absence she must be — in all senses of the word. I’m sending big, slightly-too-long hugs your way. Along with immense admiration for her to have raised amazing you while she was creating this tremendous work 🥰

Your mom sounds incredible and complicated and very much like The Incredibles' Edna: NO CAPES! Thank you for sharing her energy and her enormous artistry. I respect and honor your loss and grief. Peace to you and your family.